Who Designs Canada?

Writer: Julia Gillis

Editor: Sabrina Khan

For generations, architecture in Canada was a profession Indigenous people were largely excluded from. Until 1961, the Indian Act forced Indigenous people to choose between pursuing higher education and retaining their legal status as First Nations, a barrier that kept many generations from entering fields of urban planning and design. Even now, there are fewer than 30 Indigenous architects in all of Canada, highlighting the longstanding effect of these restrictions on the profession.

As a result, Canadian cities have long reflected imported European styles. “The past has not been recognized,” said Mr. Hickey, 47, who is Mohawk and a member of the Six Nations of the Grand River. “A lack of identity has developed in this place; we tend to import buildings from Europe, with banks that imitate Greek temples.”

This absence of representation, however, is beginning to change. A new generation of Indigenous architects is emerging, and with them a transformation of the urban landscape. Thanks to the new generation of visionaries, cities like Toronto and Vancouver are finally beginning to reflect the legacies of their native people.

An Unprecedented Surge

In recent years, this change has turned into an unprecedented surge of Indigenous-initiated architecture and landscape design initiatives, and there are growing examples of Indigenous design being integrated into existing buildings and landscapes in Canadian urban centres. Additionally, increasing collaboration between Indigenous architects and larger legacy firms is starting to change the discipline.

Since the Truth and Reconciliation Commission released its 94 Calls to Action in 2015, many public contracts have required the involvement of “at least one Indigenous knowledge carrier who can advise a design team,” noted David Fortin, an architecture professor and the first Indigenous person to direct a Canadian school of architecture.

While architecture was not explicitly named in the Calls to Action, a missed opportunity, some argue, Fortin sees design as a powerful tool for reconciliation. “Architects haven’t been the best listeners throughout history,” he said. “That’s why I see reconciliation as so important, and design as such an opportunity for it.”

Spotlighting Indigenous Architecture in Canada

Across Canada, several recent projects illustrate how Indigenous architects are redefining contemporary design.

Toronto Dawes Road Public Library

At the Toronto Dawes Road Public Library, architect Eladia Smoke, founder of the Hamilton-based firm Smoke Architecture, designed the building around the idea of a blanket, using it as a metaphor for the care and support the library provides to its community. The metaphor shaped the design, with the structure appearing to drape and fold around its interior spaces. Smoke Architecture, an Indigenous-led practice, is known for integrating Indigenous knowledge and sustainability into contemporary design.

The Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre on the University of British Columbia Campus

Formline Architecture made history when it became the first Indigenous-owned firm to receive the Governor General’s Award, one of Canada’s highest honors, for its design of the Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre at the University of British Columbia. Stylistically, the “humane and organic” timber structure stands in contrast to the surrounding concrete and modernist structures. Beyond its appearance, the design is also practical as it includes underground tubes that pump fresh air into the building, inspired by traditional birch bark systems once used to feed oxygen to fires.

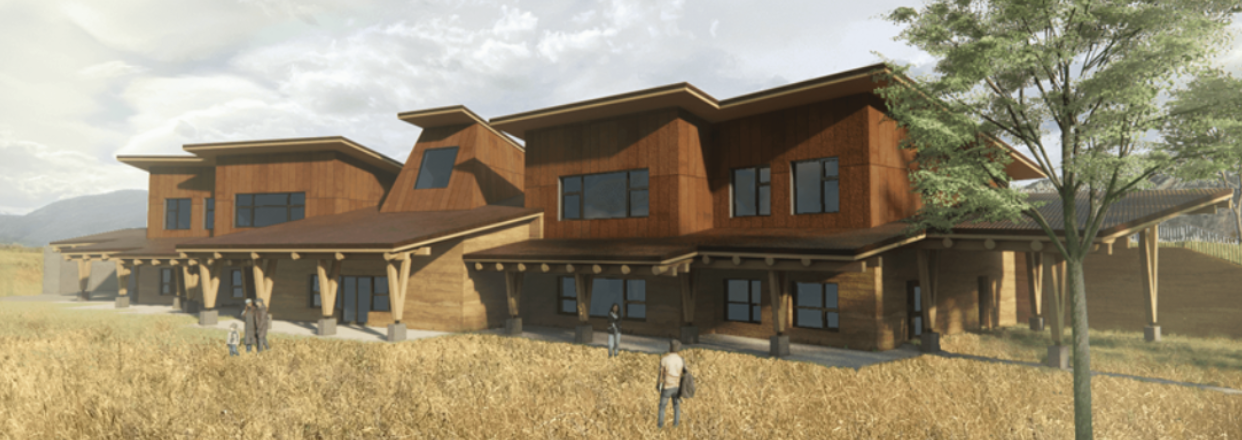

Nzen’man’ Child and Family Development Centre for the Nlaka’pamux community in the southern interior of BC

In British Columbia’s southern interior, the Nzen’man’ Child and Family Development Centre is being designed for the Nlaka’pamux Nation as a space that brings all of the organization’s services together under one roof. After wildfires devastated the town of Lytton and surrounding areas in 2021, the need for a permanent, resilient facility became even more urgent.

The new centre, located on the Inklucksheen Reserve along the Fraser River, is designed as a land-bermed structure that backs into the hillside, drawing inspiration from the traditional shieshkin, or pit house. Its red rammed-earth walls, made from local, naturally fire-resistant material, reflect the vibrant canyon rocks of the region. Additionally, the building is oriented toward the Stein Valley, home to ancient pictographs that hold important cultural stories, including a Nlaka’pamux birthing story

Ongoing Challenges:

Despite the momentum behind Indigenous-led design, barriers remain. Kelly Edzerza-Bapty, founder of Obsidian Architecture, says that during her education in industrial design and architecture, she rarely saw herself reflected in the profession, which motivated her to establish a female-led Indigenous practice.

Furthermore, although partnerships with larger firms are helping to advance Indigenous architecture, they are not always equal. Some Indigenous architects say they are brought in to meet requirements or “check the box,” rather than to lead the design process.“I’ve tried partnering with bigger firms and realized that a lot of the time, you are still tokenized,” said Kelly Edzerza-Bapty. “You are never offered equity beyond consultation, and are not in the meat of the construction documents: you are merely ‘Indigenizing’ their designs.”

Why It Matters: Representation & Sustainability

Indigenous architecture plays such an important role in representation as the design of a building should reflect not only its function, but the people who use it and the community it serves. These inclusive approaches have created authentic community projects and, more importantly, a sense of empowerment that goes beyond the building itself.

Sustainability is also central to many of these projects, particularly as communities face more frequent natural disasters. In British Columbia, recent wildfires have forced architects to rethink how buildings respond to environmental change. Some are harvesting wood charred by forest fires, a practice that repurposes strong remaining timber and also helps reduce fuel for future fires and supports forest regeneration.

Additionally, before building, many Indigenous architects will run a full-day workshop with the community they plan on serving, running model building and design thinking sessions. In this participatory approach, they’re thinking about buildings in terms of being in place for several generations, of having that longevity and durability, and therefore being inherently sustainable.

For readers interested in how design, sustainability, and reconciliation intersect, this movement offers much more to explore. If this shift sparks your interest, take a closer look around at the architecture in our city, and consider learning more about the Indigenous architects helping reshape those spaces.

References

Millette, D. M. (2019, January 3). Indigenous Architecture in Canada: A Step Towards Reconciliation. National Trust for Canada. https://nationaltrustcanada.ca/online-stories/indigenous-architecture-in-canada-a-step-towards-reconciliation

'Now We Have a Voice': Indigenous Architects Redesign Canada. (2026, February 10). The New York Times. Retrieved February 14, 2026, from https://www.nytimes.com/2026/02/06/realestate/indigenous-architecture-canada.html

Steen, E., Wahpasiw, O., & Young, P. (2022, May 1). Ten Indigenous Designers. Canadian Architect. https://www.canadianarchitect.com/ten-indigenous-designers/

Toronto Metropolitan University. (n.d.). Indigenous Architecture in Canada: A Step Towards Reconciliation. https://www.torontomu.ca/saagajiwe/sikose/architecture/